Yesterday I wrote about functional unemployment, a term LISEP uses to describe full-time workers who cannot make ends meet. LISEP also takes a broader look at the unemployment rate to measure the impact of functional unemployment on the economy.

Besides the true rate of unemployment (TRU), LISEP has also analyzed True Weekly Earnings (TWE). This accounts for inadequacies in the way the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) measures compensation. According to the BLS, weekly earnings among all workers average $1,001. Unfortunately, these statistics don’t consider the impact of part-time workers. Including the earning potential of part-time workers gives a truer picture of average weekly earnings. This is because so many workers involuntarily work fewer than 40 hours per week.

When you factor in part-time wages, the TWE for September 2021 was $846, 15.5% less than the BLS’s estimate of weekly average wages. Over the course of a year, the BLS overstates the average wage by more than $8,000.

TWE statistics show how depressed wages restrict economic prosperity. Black, Hispanic and female-headed households feel the effects of functional unemployment most keenly. For every $1 that a white male worker earns, black and Hispanic workers earn just $0.73. Female workers fare slightly better; they earn $0.78. Income disparities of this size noticeably impact the economic well-being of these households.

Impact of education on true weekly earnings

Education does make a difference in true weekly earnings. Workers with some college (including certificates and associate degrees) earned $92 more per week in 3Q2021 than workers with only a high school diploma. Sustained over a 12-month period, that would increase household income by $4,800. Bachelor’s degree holders earned nearly 50% more in Q32021 than workers who had only some college. That sounds like a lot, but while bachelor’s degree holders will avoid poverty, they could not support a dependent.

One interesting figure may explain why community college enrollment is declining. Since 2000, earnings growth among workers with some college (which includes certificates and associate degrees) inflation-adjusted earnings have declined by 8%. Earnings growth for workers with this educational background dipped below 0% in mid-2005 and have not reached positive territory since.

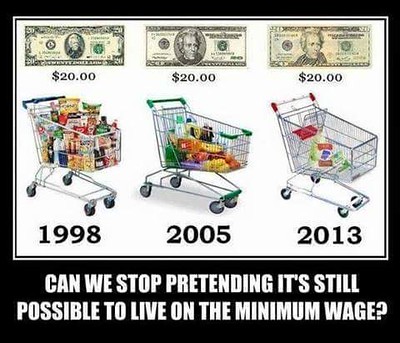

The devaluation of workers with certificates and associate degrees took a firm hold during the Bush (II) administration, but it has nothing to do with declines in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Comparing GDP growth between 1998 and 2021 shows that while the GDP has grown by an inflation-adjusted 42% over that time, the average inflation-adjusted weekly wage has increased only by about 8.5%. In other words, while corporations and individual owners have benefited from the growth in worker productivity, the workers who produce goods and provide services have not.

Community colleges cannot participate in the devaluation of educated workers

The devaluation of educated workers is not limited to those with some college credit. Earnings growth among those who hold bachelor’s and advanced degrees rests at a net increase of 2% between 2000 and 2021. Although earnings growth is currently positive for these workers, their earnings growth was entirely negative between 2007 and 2019.

Workers who have no high school diploma have enjoyed the largest earnings growth during this period. This group includes teenage workers who have not yet graduated from high school, as well as adults who lack a secondary school credential. The growth in wages may be largely controlled by statutory minimum wage increases among the states rather than labor demand forces in the marketplace. Earnings growth for this group turned positive in 2016.

Community colleges cannot continue to contribute to the negative true weekly earnings environment by offering certificates and degrees that do not produce living wages, or by encouraging students to pursue near-worthless degrees in these fields. Community colleges must develop programs that train workers in high-demand, high wage fields. Period. At the same time, they must avoid training programs for fields where demand for workers is high only because employers want to pay poverty-level wages.

This is exactly where WCC’s certificate strategy fails its students and Washtenaw County as a whole. By supporting the devaluation of an educated, trained workforce, WCC is counteracting growth and inhibiting equalization in economic prosperity. That’s not why Washtenaw County taxpayers have invested in WCC.

Photo Credit: Leigh Blackall, via Flickr