The WCC President claims that WCC’s shrinking enrollment motivates her search for additional revenue. Her solution is to build a taxpayer-funded hotel and conference center. She can point to numbers that show that WCC’s enrollment has dropped over the last 10 years. That’s true. Further, overall community college enrollment in Michigan has dropped from about 210,000 students in the 1980’s to about 170,000 students today.

It’s not enough to look at numbers when considering community college enrollment. Enrollment at a community college changes predictably with the economy. At a four-year institution, enrollment is pretty steady, no matter what the economy does. Further, four-year universities usually have more applicants than available space. Their undergraduate applicants are usually 17-22 year olds who intend to earn a four-year degree.

Two year colleges are not like that. For the most part, they feature a non-competitive application process. Their enrollment goes up when the economy gets bad, and goes down when the economy recovers. The typical applicant is hard to describe because few of them are traditional students. In WCC’s case, a high percentage of its students are older than 30. WCC also attracts a higher proportion of minority students, retraining workers and women entering or re-entering the workforce.

When the economy is good, WCC’s shrinking enrollment shows up. That makes sense because WCC’s programs largely focus on training workers. When the economy is good, fewer workers seek training because they can get a job without it. When the economy sours, fewer jobs are available. High school graduates can’t readily enter the workforce and teen unemployment soars. When this happens, would-be workers take the opportunity to study while waiting for their job prospects to improve.

What’s really happening with WCC’s shrinking enrollment

Currently, the economy is experiencing a historically long expansion period. Because the economy has grown significantly since the end of the Great Recession, WCC’s shrinking enrollment pattern on full display. Its enrollment is ‘”low” compared to its recessionary high water mark, but it is steady.

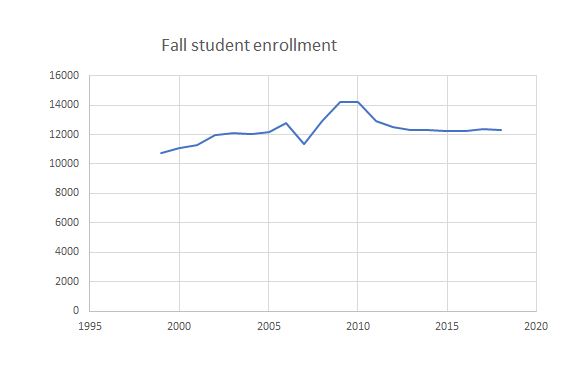

The graph below shows the WCC fall student enrollment trend from 1999-2018. Enrollment spikes during and immediately following a recession, then returns to stable levels. WCC’s enrollment inversely tracks the economy.

In a strong economy, revenue from student tuition and fees drops, but increasing property tax revenues fully offset this loss. WCC does not suffer financially due to declining enrollment during a boom economy. Additionally, WCC has been very consistent about raising tuition rates over the last several years. Tuition revenue has increased, even with WCC’s shrinking enrollment.

A complete economic cycle features expansion and contraction; it drives students into or out of the community college. Unlike a university or a K-12 school system, community colleges enroll students of all ages. These students could be dual-enrolled in high school, high school graduates, college graduates, middle-age retraining workers, or workers re-entering the workforce after having been absent for a while. Put another way, the community college always has a very large, age-independent applicant pool available to it. As long as WCC offers relevant, high quality technical and occupational programs, it will attract students in any economic climate.

The president’s message matters

The three conditions that can make enrollment drop are a declining population, a good economy and bad academic programs. Washtenaw County’s population is not shrinking; it is growing. That leaves a good economy and bad academics to account for WCC’s enrollment declines.

Enrollment revenue accounts for about 25%-30% of WCC’s annual revenue. So, when the community college president says:

“– the enrollment is not going to be where it always has been. And it is going to continue to be more challenging. “

She is saying that she is concerned about this element of WCC’s overall funding. Because Washtenaw County’s population is growing, either she is concerned that:

A. The economy is going to stay good indefinitely, causing a long-term drop in student tuition revenue, or

B. WCC’s programs are deficient and cannot attract students.

We already know that a good economy generates additional tax revenues that offset the loss in student tuition.

If she’s saying that WCC’s enrollment decline is the result of bad academic programming, that’s a whole other problem that needs to be addressed immediately by the Board of Trustees. Heads should roll, starting at the top.

In reality, WCC’s enrollment will continue to do what it has always done – it will change with the economy. And tuition revenues will rise and fall. That’s how the community college funding mechanism works. And the mechanism is working as designed. WCC does not need to make up “losses” in tuition revenues because property tax revenue increases have taken care of that.

WCC’s shrinking enrollment doesn’t hurt the College

In a bust, enrollment will increase, along with the revenue from tuition and fees. In the meantime, WCC absolutely must avoid any revenue generation scheme that relies heavily on a boom economy. A hotel and conference center will only serve as a drag on WCC’s finances during a bust. We cannot afford to divert educational funding to prop up a hotel during a soft economy.

Washtenaw County taxpayers must display the fortitude that the WCC Trustees have not. Using the millage renewal on March 10, voters must send a message that WCC’s shrinking enrollment today is far preferable to a hare-brained revenue scheme that will destabilize the College in the next economic downturn.

Photo Credit: Future Atlas, via Flickr.com