There has been a lot of debate lately on the value of remedial classes. As it turns out, adult learners who get placed in remedial classes not only don’t benefit, but they also tend to drop out without completing a credential. Instead, research shows that co-requisite learning is a better approach for students who are particularly weak in basic reading, writing and math skills. But do remedial classes have a place somewhere in the education system? Research from Israel may hold a clue.

Researchers there reviewed the results of remedial classes offered to 16- and 17-year-old students as part of a “catch-up” effort. In the US, students who are in danger of failing altogether or dropping out of school usually land in remedial classes. In Israel, however, remedial classes attract students who could perform at a higher level with additional instruction.

The original plan targeted 130 low-income schools and incorporated 4,000 students. Because the classes took place after school, they were offered in a small-group format. This enabled the students to receive individualized instruction from their regular classroom teachers. (The teachers received overtime pay for their participation.)

The program cost the government about $1,000 per student per year and became a casualty of politics. However, the researchers wanted to find out what happened to the students who participated in the program. They used a comparison group, which included similarly situated students who did not receive extra help in high school.

Remedial classes had significant long-term benefits

In the short term, the program increased (by 13%) the number of students who passed Israel’s university entrance exams. But the benefits continued. Compared to the control group, a higher percentage of students attended college at a higher rate and completed more college coursework. The remediated students also earned more money and performed better economically than their parents did. They also had higher marriage rates.

While the program cost the government an extra $1,000 per participant, their higher earnings as adults enabled the government to recover those costs (in the form of higher income taxes) in about eight years. In other words, by the time the participants were 30, the government had already recovered its initial investment in them and were collecting more taxes.

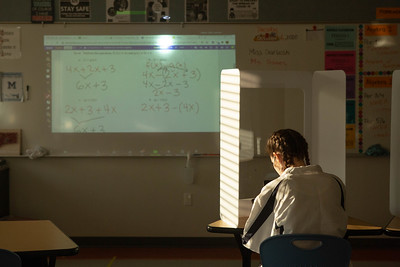

Reconnecting high school students to in-person learning

So, it seems like there’s a summertime opportunity here for WCC. Small-group math programs targeted at high school students who would like to perform at higher levels. Maybe as part of SAT preparation, maybe just catching up from the previous year’s math instruction.

Such a program may be even more interesting for students coming off of a year or more of virtual instruction. It’s a benefit all around.

For the students, they receive additional instructional time with a teacher in a small group setting. The students who participate will likely perform better on college entrance exams, are more likely to attend college and are more likely to perform better while in college. They’re also likely to earn more after leaving college.

The College would benefit. First, the students are paying for tailored instruction. It gives the College the opportunity to put more adjuncts and part-time instructors to work. It increases the chance that the participating students will enroll in WCC credit classes. Such a program directly ties to the College’s mission, and it improves the college-readiness of area students. Further, it lays the foundation for STEM careers. Overall, it benefits the community much more than a failing fitness center or a half-empty hotel would.

It’s a great investment in the local community, and it’s probably a better way for WCC to spend its summers.

Photo Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action, via Flickr