Yesterday, I wrote about the difference between the federal poverty level and a living wage. I also wrote about why it is important for community college administrations to remain vigilant about the earning potential of their academic programs. By itself, vigilance is not enough. Community college administrations must act by regularly eliminating low-wage academic programs from their catalogs and replacing them with higher-wage options.

Unfortunately, instead of doing this, community colleges have focused their efforts on growing the ranks of the administration, neglecting the facilities, and chasing “other revenue” while simultaneously reducing the number of full-time faculty members on staff. This approach not only consumes resources and dilutes the quality of instruction, but also limits the community college’s capacity to increase the region’s economic diversity.

How does this play out in real life? The US Census Bureau recently released the 2021 data from its annual American Communities Survey (ACS). ACS is a miniature version of the Bureau’s decennial census. Each year, the US Census Bureau randomly selects American households to participate in the survey. By law, these selected households are required to complete the survey tool.

The ACS gives a better picture of wage and earnings data. According to the ACS data, in Michigan in 2021, the lower bound of the “middle class” began at $42,544. Additionally, the average wage earned by a person with either “some college or an associate degree” was $40,934. This is exactly where the “vigilance” comes in. The average associate degree does not have enough income potential to allow people to join the middle class. This would not be true if community college administrators routinely canceled low-wage academic programs. Instead of watching out for the students, community college administrators watch out for employers. (And we’re all worse off for it.)

ACS reveals danger of inaction on low-wage academic programs

Males in the survey earned an average of $50,174 while females earned an average of $34,340. This should give community college administrators heartburn for at least three reasons.

First, the Census Bureau equates “some college” and “associate degrees.” Implicitly among the Census Bureau’s data scientists, dropping out of college is indistinct from completing an associate degree. Data scientists are usually pretty good at parsing the difference between “A” and “B.” So, when a data scientist feels comfortable combining “some college” and “associate degree” in the same category, it should raise concerns among those who are trying to sell community college programs as a viable economic pathway.

Second, the number of males enrolled in post-secondary classrooms has declined remarkably in the past decade. Males in the “didn’t-finish-college/finished-an-associate-degree” category are earning 20% more than the combined average of all college dropouts/associate degree earners. The ACS doesn’t parse the category further, so it’s not possible to say whether the associate degree earners out-earned the college dropouts or vice versa. But there’s not enough daylight between them to make a difference.

Third, females with “some college or an associate degree” earned 16% less than the median salary for all respondents in this group. That should also set off alarms because so many women enroll in community colleges and graduate with associate degrees. Creating low-wage households isn’t the goal of community colleges; yet, that appears to be exactly what’s happening. Women with associate degrees earn nearly 20% less than they need to crack the middle class in Michigan.

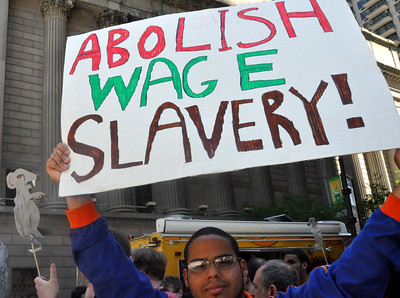

Community colleges need to exit the business of generating low-income households by leaving low-wage academic programs behind. Everyone needs the means to earn a living wage, but committing women to living on the margins is unconscionable.

Photo Credit: Michael Fleshman , via Flickr