A popular theory is that an unstable job market drives community college enrollment. Specifically, displaced workers return to school after unexpectedly losing their jobs. Community college enrollment seems like a logical reaction to job loss, but research shows that’s not what happens among most people who lose their jobs.

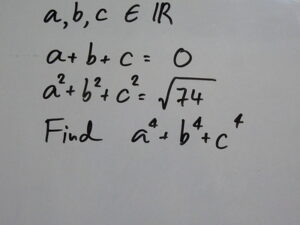

Researchers from Columbia and Stanford Universities examined community college enrollment following mass layoff events. They found that while community college enrollment may increase, the newly enrolled students don’t typically come from the cohort of workers who lost their jobs. In fact, only about 1% of laid off workers elects to return to the classroom. For those who do, about 30% complete a credential. Additionally, the manufacturing sector accounts for virtually all of the “enrollment effect.”

The researchers note that most workers who return to school enroll only part-time. This may explain why most of them do not complete a credential. Additionally, the lowest paid displaced workers are most likely to return to school.

Follow-up one year after displacement shows that about 15% of displaced workers remained unemployed. Older workers in the cohort who may be working typically make less than they did when they lost their jobs.

Interestingly, the presence of a local public higher education institution did not really influence the decision to enroll if a for-profit college or university was also located nearby. In that case, displaced workers who enrolled in a post-secondary school often chose the for-profit institution over less costly publicly funded options.

The authors speculated that for-profit institutions are fundamentally better at taking advantage of federal funding designed to assist displaced workers and workers who may be retraining for other reasons.

Manufacturing accounts for most community college enrollment following layoffs

This isn’t good news for community colleges that may be counting on the trough of the economic cycle to boost their enrollments. Community college enrollment may rise, but the students who enroll are not those directly displaced by their employers. It also means that non-manufacturing sectors that experience mass layoffs are not likely to contribute positively to community college enrollment.

This supports the claim that currently, community colleges do not provide a viable return path to the workforce for the vast majority of displaced workers. The economic cycle might be a better predictor of community college enrollment if community colleges reliably used its rise and peak to develop new, high-wage, high demand programs. If they pursued this strategy, they would have programs ready to go that would enable displaced workers to earn at near or above the same rate they were earning when they lost their jobs.

The rise and peak of the economic cycle provides both the time and the resources community colleges need to develop new programs. Failure to use this time appropriately is the fault of the administration, and the oversight body should hold them accountable for being unprepared to respond to the eventuality of an economic downturn.

It’s really not that hard. If you want the benefit of the bottom half of the economic cycle, you need to work the top half of the cycle accordingly.

Photo Credit: Oregon State University , via Flickr