Yesterday, I wrote about the vast and growing number of post-secondary credentials available in the United States. Today, there are nearly 1.1 million discrete credentials, ranging from doctoral degrees to digital completion badges. In 2018, when the Credential Engine, a non-profit organization that has taken on the task of cataloging all available credentials, released its first count, the group found 334,114.

Credential issuers are just as varied. They range from accredited, degree-granting institutions to product vendors and service providers. Every credential represents a challenge to the primacy of traditional universities and colleges. Until recently, when people wanted to study particular subjects or master specific skills, they either turned to a higher education institution, learned the subject matter or skills themselves, or learned apprentice-style from someone else who had mastered the materials.

Today, there is growing debate about what constitutes post-secondary education, who is entitled to deliver it, who is entitled to accredit the provider and even if a formal education is necessary. The US Department of Education has set its sights on for-profit education providers, in an ongoing effort to eliminate high-cost, low-value credentials.

Private education providers have staked a claim on occupational and vocational education programs. Although many traditional providers – like community colleges – complain that these institutions are encroaching on their territories, the truth is that they provide services that community colleges don’t.

For-profit institutions are problematic. They have incredibly high costs to the students, high federal student loan default rates, non-transferrable credits, low-quality learning facilities, and poor academic reputations. But they also can offer occupational training that community colleges don’t. They can offer flexibility in course enrollment and delivery, which many public institutions are only now beginning to offer. In some cases, they can even register higher completion rates than their non-profit counterparts do.

Community colleges initially provided occupational and vocational education to adult learners. Congress hoped they would eliminate the country’s need for highly skilled immigrant workers.

But occupational education is expensive. It often requires specialized equipment, non-standard classrooms, and lots of space. It also requires highly skilled, experienced instructors who are willing to teach rather than work in the field. Additionally, occupational and vocational programs must remain current as industries adopt new technologies. They can’t stagnate; if they don’t keep up with the changes, the programs become useless to the industries they’re trying to serve.

Misguided administrators often complain about the expenses associated with vocational programs. They don’t recognize that the public funds these programs specifically because they are otherwise too expensive. When community colleges voluntarily close occupational programs, they intentionally or unintentionally cede ground to private, for-profit schools. Eliminating lower-cost educational options works to the benefit of these providers and makes it harder (and more expensive) for the lower-cost providers to re-enter the educational marketplace.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks the occupations in highest demand every year. If you compare the list of today’s 20 most in-demand occupations with those from 2011, you will find that exactly one position – physical therapist assistant – appears on both lists. The 2023 list is otherwise completely different. It speaks to the pace with which employment demands change, and the need for community colleges to keep up with changing labor market demands.

For all their numerous faults and failings, for-profit colleges and universities do a much better job (at least on the surface) of spotting and responding to emerging opportunities in the labor market. Although their goal is to make money, they fill the holes that community colleges largely ignore.

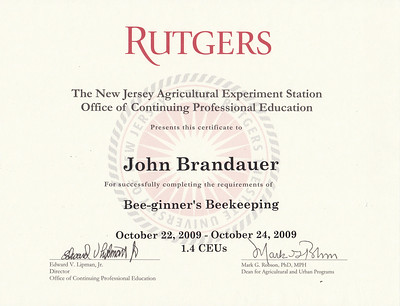

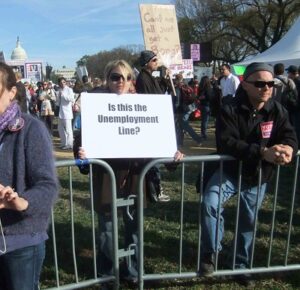

Photo Credit: John Brandauer , via Flickr