Yesterday, I wrote about the severe flooding risk that the WCC campus faces. The 15-year flood risk profile for the campus is significant because the WCC Master Plan calls for the construction of a hotel and convention center on campus. It also calls for the development of retail space in the TI parking lot.

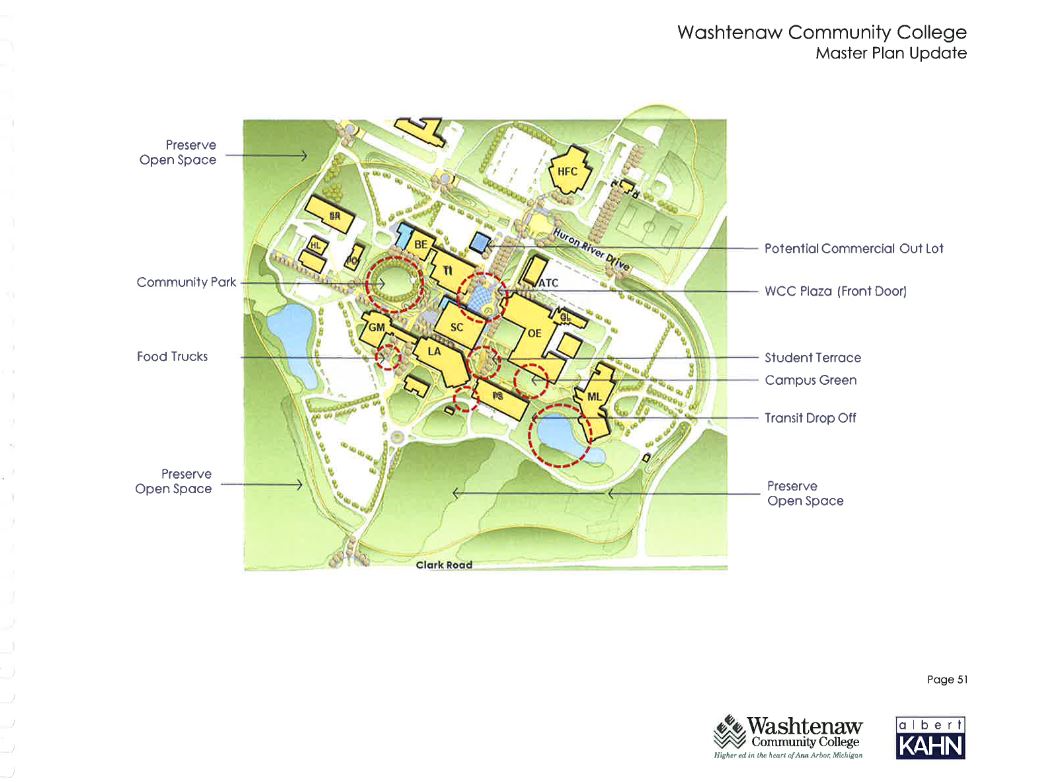

This drawing, from the current WCC Master Plan, shows the location of the proposed retail space in the TI parking lot.

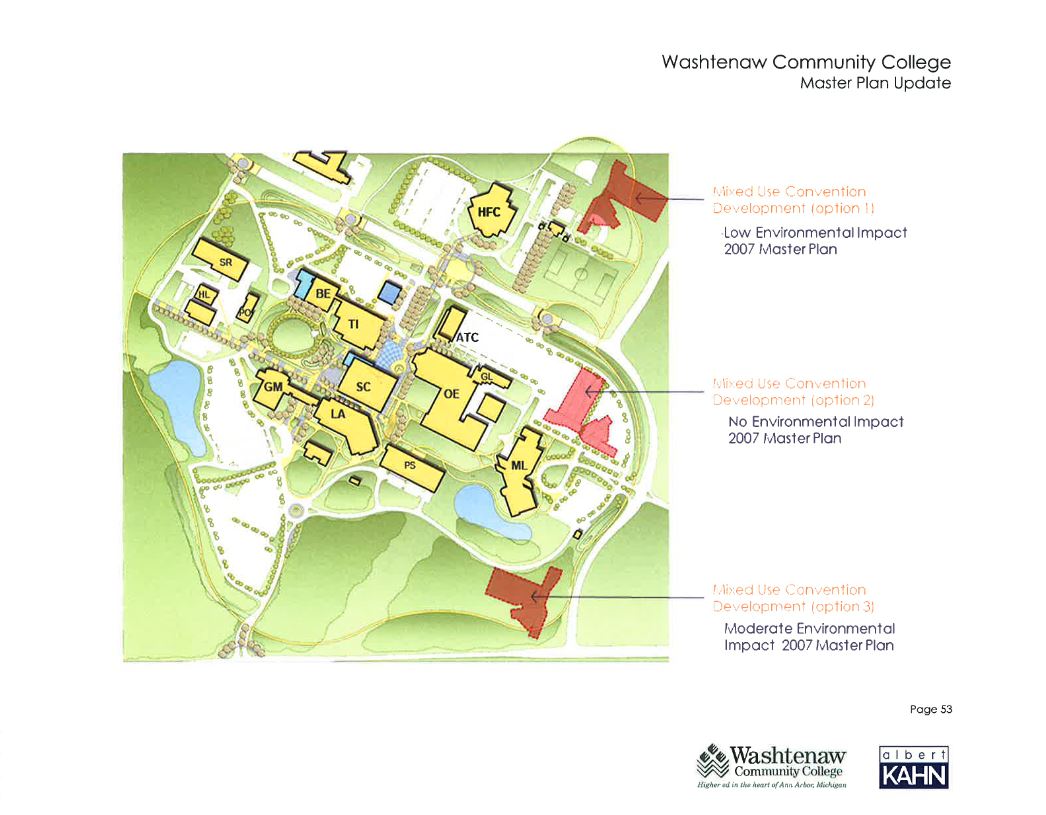

Also from the current WCC Master Plan, this drawing shows the potential location(s) of the hotel and conference center on WCC’s property.

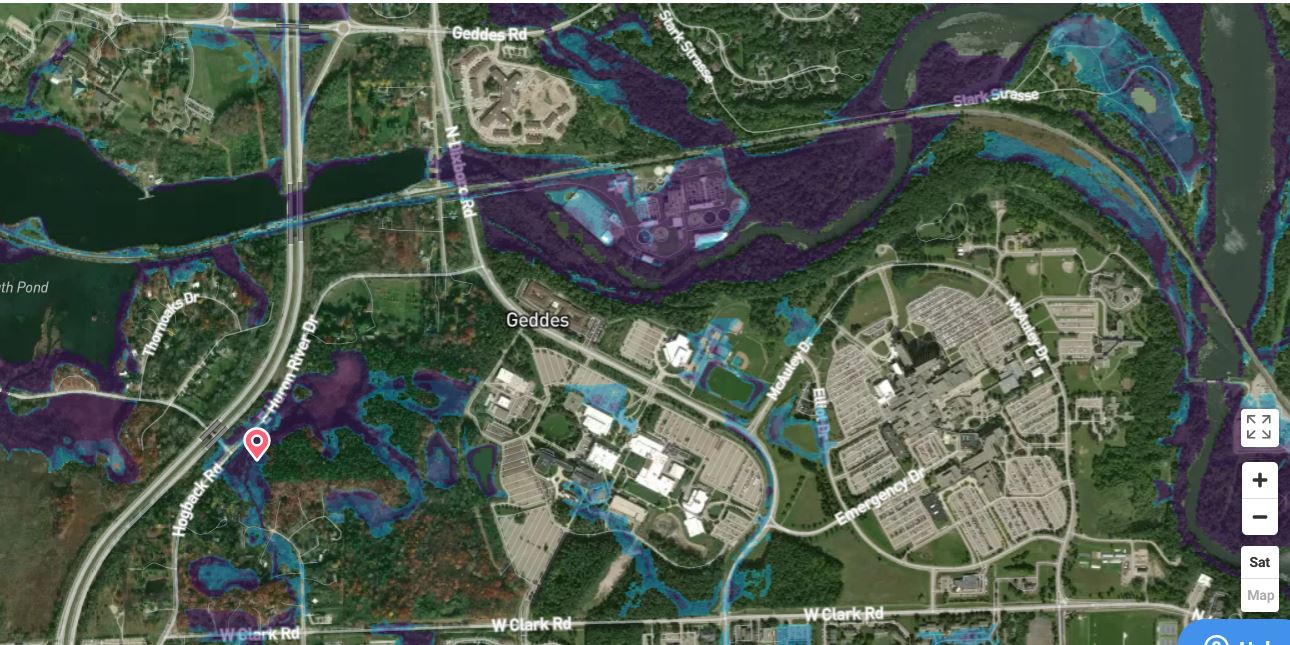

This drawing shows the 15-year flood profile for the campus.

From the drawing, the TI parking lot and two of the three proposed hotel locations overlap the campus’s flood profile. The blue and purple highlighting show the potential severity of flooding in a high-water event. Purple is more severe than blue.

This isn’t the only concern that significant flooding could bring to the campus. The model also shows the same severe flood risk for the Ann Arbor Wastewater Treatment Plant next door.

So, what happens when a wastewater treatment plant floods?

City of Galveston

Wastewater treatment plants are not immune to flooding. Severe weather (hurricanes, flash floods, etc.) can create significant problems for these facilities. On September 13, 2008 Hurricane Ike caused $3.5M in damage to Galveston’s wastewater treatment plant. That amount included $1.5M for hazard mitigation. Two weeks prior to Hurricane Ike, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality adopted revised rules for reinforcing wastewater treatment plants to withstand 100-year flood events. The cost of upgrading the damaged plant to the new state standards was nearly $72M.

Following Hurricane Ike, the City of Galveston applied to FEMA for $72M in federal assistance that would enable the plant to meet the new, more rigorous standards. FEMA denied both the initial request and the subsequent appeal. In its denial, FEMA explained the rejection. fThe federal agency was not responsible for financing the cost of bringing the existing plant up to the state’s recently revised standards. Rather, it would only support the repair of the plant’s damaged components.

City of Conway

In September 2018, Hurricane Florence disabled the Conway Wastewater Treatment Plant in Conway, SC. As a result, untreated wastewater was discharged into the Waccamaw River. The plant was non-operational for about 24 hours, during which time, the plant dumped millions of gallons of raw sewage into the river. The plant had also been damaged by Hurricane Joaquin in 2015 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016. The Grand Strand Water and Sewer Authority (the operator of the Conway Wastewater Treatment Plant) applied to FEMA for financial assistance to relocate the wastewater treatment facility outside of the floodplain. After determining that moving the plant was not possible, the GSWSA opted to seek funds to raise the plant to a height two feet above the 100-year flood level. (Hurricane Florence was a 1,000-year flood event.) Earlier this year, GSWSA was awarded a $6M state-level grant to assist in the process of flood mitigation.

City of Flint

In August 2019, flash flooding caused the settling tanks at the Flint Water Treatment Plant to overflow. The overflow settled into the ground around the flooded tanks and reached the storm sewers, which discharged the overflow into the Flint River.

If you think this won’t happen in Ann Arbor, note that the Ann Arbor Wastewater Treatment Plant reported sewage overflows in 2019 and 2020 following heavy rains.

The lessons here are simple: wastewater treatment plants will flood in high-water events. Those spills go into adjacent rivers and surrounding areas in water volumes that could be measured in millions of gallons per day if the plant were fully compromised. FEMA is neither fast nor helpful when it comes to cleaning up after a flood.

From the maps above and from Board conversations regarding the Master Plan, the Board would prefer to build a hotel on the parcel of land closest to the Huron River. They prefer this parcel over the other two options because it is in Superior Township. They either do not know or do not care that their preferred parcel of land is the one most prone to flooding. Further, should a sewage spill occur, a hotel on that parcel could be a total loss.

The risk of flooding on campus is real and only grows more likely with the passage of time. If the Board of Trustees refuses to act in the clear interest of the taxpayers, voters must remove them. We do not need Trustees who refuse to protect the taxpayers from WCC’s ridiculous financial misadventures.

Photo Credit: SA Water , via Flickr