In the past several years, there’s been a lot of hand wringing about the state of community college enrollment. Somewhat ironically, it’s being done by the very people who should be best positioned to do something about that.

The economic outcome of a community college degree is both clear and damning: fewer than half of graduates with an associate degree earners and about one-third of people with a non-degree certificate earn more than $35,000 per year. Yet some community colleges – like Washtenaw Community College – are pushing certificate programs harder than ever. Evidence clearly shows that associate degree holders stand a better chance of earning more money, but WCC directs students into certificate programs with lower economic potential.

This information is not lost on students. Millennials who have earned a bachelor’s degree have seen their incomes rise because of their four-year degrees. Millennials who have earned an associate degree have seen their incomes tank. Their two-year degrees earn them barely more than their contemporaries who earned only a high school diploma. Today’s high school graduates view higher education as a risk – one not worth assuming debt for. Unfortunately, fewer than 20% of children today have a 529 college savings plan or similar college fund. Only about one-third of undergraduate students nationally qualify for Pell Grants. And because Generation Z is debt-averse, they’re not willing to borrow to complete a college degree.

Community college enrollment problem requires two solutions

Fixing community college enrollment comes down to two things: fixing occupational education programs so graduates can earn a living wage, and fixing the transfer pathway.

Community colleges have relied on local employers to tell them what to teach. Unfortunately, most local employers don’t know what skills they want or need. Moreover, employers have a vested interest in limiting the wages of their employees. This directly opposes the students’ needs and goals. Expecting actionable advice from employers is misguided at best.

For better or worse, employers try to move with the market. Community colleges can never move fast enough to react to market-level changes. To compensate, two-year colleges have created non-degree certificate programs, which students can earn in weeks or months.

This hasn’t had the desired effect. Employers don’t recognize these credentials as worthwhile. They produce workers whose knowledge and skill gaps are too great for on-the-job experience to remedy. Employers pay certificate-holders even less than they pay those with associate degrees. In the end, the certificates have limited value.

Community colleges shouldn’t try to adapt to employers’ instantaneous talent needs. Instead, they should aim to educate students more broadly and help them develop skills that will support employers’ shifting demands. Programs should focus on identifying and addressing longer-term industry trends. Let employers develop more specific employee training that meets their unique needs.

Fixing the transfer pathway

While three-fourths of community college students enroll with the intention of transferring to a four-year program, fewer than 15% of these students actually graduate with a bachelor’s degree.

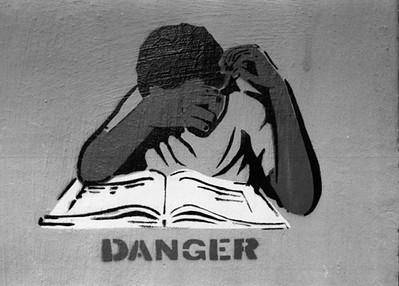

Just as occupational students face the real risk of not being gainfully employable after graduation, transfer students contend with the high likelihood that they will never complete a bachelor’s degree. Community college is not so much an opportunity as it is a minefield. Increasingly, it is one that prospective students simply don’t want to attempt.

It is easier to enroll directly into a bachelor’s degree program, and students are more likely to graduate. Fixing the transfer pathway involves acknowledging that university standards typically rise over time. Accordingly, community college students cannot arrive in a more academically rigorous environment unprepared to succeed. Creating a transfer pathway that rises to the academic rigor of a university environment is likely the best way to ensure that students who intend to complete a bachelor’s degree achieve their desired outcome.

It is possible to fix community college enrollment. Community colleges are being torn apart by the wild gyrations of directionless employers as they attempt to keep pace with a largely incomprehensible market. Community college administrators need to carefully re-examine their quick-start/low-wage strategies to see whether they really further the goals of the community college’s mission.

Photo Credit: Jacques Meynier de Malviala , via Flickr