I read an opinion piece a while back regarding mergers among higher education institutions. The author’s point was that schools that really needed to merge often started the process far too late. That strategy leaves little room for failure, and often results in school closures.

Mergers and closures are the most likely outcome for a large swath of higher education institutions in the relatively near future. As I wrote about a couple of weeks ago, Michigan’s public higher education institutions (combined) are running at about 55% capacity. “Right-sizing” the higher education landscape involves one of two approaches: increasing enrollment or closing schools.

Increasing enrollment doesn’t sound likely, although technically, there are enough traditional college-age students to give this approach a run for its money. Population isn’t really the problem, although it doesn’t help. Higher education institutions have lost their value propositions, thanks to their overwhelming attendance costs.

A bachelor’s degree is still the ticket to the middle class. Estimates vary, but a common one says that a person can earn $1M more in lifetime earnings on average with a bachelor’s degree, compared to a person who has only a high school diploma. Over a 40-year career, that’s $25,000 more per year, or $12 more per hour than a worker without a four-year degree.

That $12 makes a major difference, but a better paycheck isn’t the only thing workers look for. The Pew Research Center’s research on job satisfaction points out that lower-wage workers also receive fewer employer-paid benefits. This lower tier of employer-paid benefits decreases job satisfaction and contributes to a lower level of employee wellness.

Higher education must adopt a student-focused strategy

When higher education institutions – particularly community colleges – go all-in on training workers for low-wage work, they commit their graduates to a lower level of job satisfaction and lower level of overall wellness. They commit their alumni to working longer hours for less pay, saving less for retirement, having fewer paid vacation and sick days, fewer opportunities to acquire new skills, and fewer prospects for promotion. If you’re a community college, that’s not a good enticement for people who have already experienced the pain that low-wage work generates.

To make community college enrollment as attractive as possible for as many people as possible, a two-year education must represent a real opportunity to escape the world of low-wage work. Community college administrators must clearly understand that a living wage is a moving target. They must constantly evaluate their programs using a yardstick that provides a standard measure of the student’s best interest. When a program no longer delivers the highest possible value to the student, it must either be reworked to improve student outcomes or retired. That is literally the only way a community college is going to attract students.

Tomorrow, I’ll look at the other strategy: school closures.

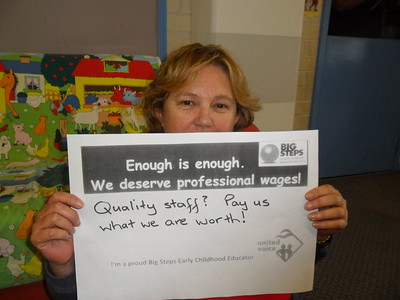

Photo Credit: United Voice , via Flickr