Yesterday, I looked at real estate valuations inside and outside the Greenbelt. The big winners in residential real estate valuations were almost all directly adjacent to the City of Ann Arbor. Where there are winners, there are also losers. Bridgewater, Manchester City, Barton Hills, Sylvan Township and Manchester Township all saw losses in residential real estate valuations between 2003 and 2023. Most other Washtenaw County communities had increases that were lower than the county average increase.

Sylvan Township’s dramatic losses in valuation occurred when Chelsea incorporated as a city in 2004. Manchester also incorporated into a city in November 2023, but the impact of that decision is not reflected in these numbers. Incorporation isn’t always a losing proposition. The Village of Dexter incorporated into a city in 2014, and residential valuations in both the city and township rose well above average.

So, what happened to residential real estate values in eastern Washtenaw County? In Ypsilanti Township, which was not a Greenbelt city – property valuations rose nominally (1%) between 2003 and 2023. In Ypsilanti City, residential valuations remained essentially flat, rising only two-tenths of one percent.

The comparatively low increases trace back to 1994’s Proposal A. Prior to 1994, a property’s State Equalized Value (SEV) determined its property taxes. Proposal A limited annual residential property taxable value increases to the lower of the rate of inflation or 5%, as long as the property ownership did not change.

The SEV, which is the State’s best estimate of the market value of a residential property, is not capped and changes with the market. If the SEV of a property falls, but remains higher than the property’s taxable value, the property’s taxes will still rise. Property taxes only decline when a property’s taxable value equals its SEV, and the SEV subsequently declines.

Proposal A, Great Recession Deliver 1-2 Punch

In the 30 years since the passage of Proposal A, inflation has exceeded 5% just once – in 2022. That means Michigan’s residential property tax cap was limited to the rate of inflation in all but one year. In Ann Arbor, property valuations (SEV) have risen by 36% since the inception of the greenbelt. It has created a large gap between an Ann Arbor property’s SEV and its taxable value. It also explains why most Ann Arbor residents didn’t see a drop in their property taxes during the Great Recession, even though their property values (briefly) declined.

In Ypsilanti, property values rise much more slowly, so the gap between a property’s SEV and its taxable value is much smaller. During the Great Recession, the SEV and the taxable values of most residential properties in Ypsilanti and Ypsilanti Township equalized, and then continued to drop.

The road back for these areas has been rocky. A property’s SEV is never capped; it’s based on the estimated market value of the property. Because there are no limits on how far the SEV can fall, there are no limits on how far a property’s taxable value can fall. But the rules regarding increasing taxable values still apply when a property’s value begins to increase again.

In Ypsilanti and Ypsilanti Township, following the Great Recession, SEVs and taxable values were stuck in lockstep for several years. Even when property began rising again, Proposal A limited the tax revenues that these municipalities could collect, which resulted in noticeable cuts to residential services.

Washtenaw County Taxable Values, Before and After The Great Recession

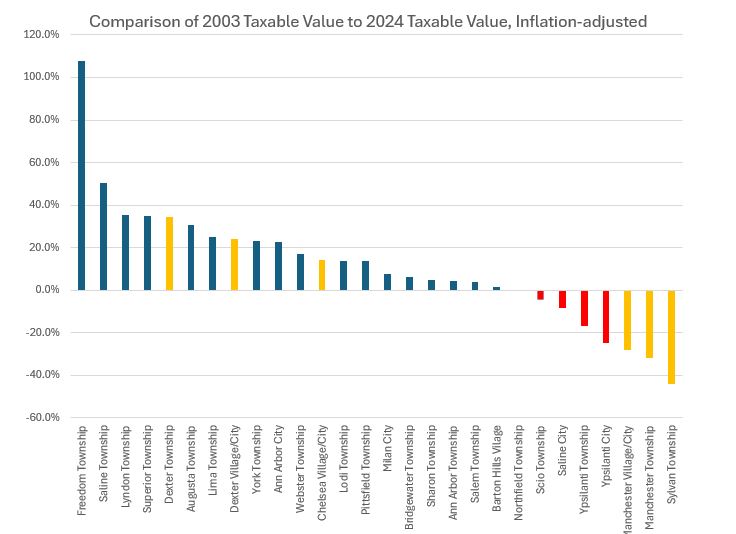

What did Proposal A do to these communities during and after the Great Recession? The chart below shows a comparison of the taxable value of properties in Washtenaw County in 2003 to the taxable value of properties in 2024.

Most communities in Washtenaw County (shown in blue) have recovered from the disastrous Great Recession and now collect more money (adjusted for inflation) today than they did in 2003. However, an unlucky few communities (shown in red) collect less in property taxes today than they did in 2003, when the 2003 taxable valuations are adjusted for inflation.

The chart also highlights the villages (in gold) that incorporated to cities. Although it seems that the newly created cities have done well, and their previous townships are now suffering, this is an artifact of the data, which may not accurately represent the status of these townships.

Those five communities in red – Northfield Township, Scio Township, Saline (City), Ypsilanti Township and Ypsilanti (City) illustrate why we need WCC to focus on creating programs that can attract new employers, deliver high-wage, high demand jobs, and enable residents currently on the margins to thrive – even as their communities collect less money for services that could otherwise improve the quality of life in these places. They cannot afford to have WCC waste tax dollars on low-wage programs, additional executives and consultants, and non-essential services.

Because not every community in Washtenaw County is rich.

Photo Credit: BasicGov, via Flickr