If you research what people want from a job, you’ll find a lot of “aspirational” stuff. Meaningful work. Respect. Well-being. Work-life balance. The opportunity to do what the worker does best. Diversity, equity, and inclusion. You’ll also find some more standard expectations: money, job security. But for 42% of people aged 59 and up who are still in the workforce, they should be looking for help with their retirement savings.

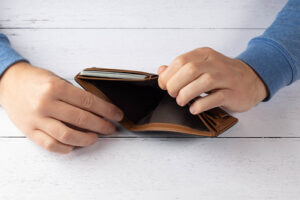

According to data collected by the US Census Bureau in 2020, 42% of Baby Boomers have no retirement savings.

As in none.

Nearly half of those closest to retirement have saved nothing for that near-future when they no longer work (or no longer can work. Most Boomers who have not yet retired can receive full Social Security benefits at age 67. A few workers can begin collecting these benefits at age 66 and 10 months. The average Social Security check (as of February 2023) was $1,694. That’s $20,328 and would be equivalent to an hourly wage of about $9.75 per hour. Retiring early means the monthly benefit would be discounted for the remainder of the recipient’s life.

By itself, that’s a great reason to ensure that people earn a living wage. Lack of retirement savings is a substantial drag on the individual and is a burden on society. Those without retirement savings consign themselves to working in what should be their retirement years. Additionally, those without retirement savings tend to accumulate debt later in life. In 2016, 60% of American households headed by senior citizens reported having debt. The average debt among older Americans exceeded $30,000.

Job changes impact retirement savings

Limited income among older workers isn’t the only problem they face. The Bureau of Labor Statistics conducted a longitudinal study of about 10,000 people born between 1957 and 1964. The subjects answered questions regarding work and non-work experiences, education, training, income and assets, health, and other characteristics. These participants represented the last of the Baby Boomers and were first interviewed by the BLS in 1979. Since that time, the BLS has remained in contact with the participants, and has collected updated data from this group.

Among the participants’ employment experiences, the BLS found that between the ages of 18 and 54, the participants held an average of 12.5 jobs. Between the ages of 18 and 24, participants reported that they had held an average of 5.6 jobs. Between the ages of 25 and 34, that number fell to 4.5 jobs on average. For workers between the ages of 35-44, that number fell farther, to an average of 2.9 jobs. By the time the participants reached age 45-54, the average number of jobs fell to 2.1.

This is significant because it shows that as workers age, they become less employment-mobile – either by choice or necessity. If they’re also in a low-wage job, they’re statistically likely to stay there, even when remaining in a position is not in their best financial interest. They end up on a crash course with poverty in retirement.

Community colleges could help mid-career workers

It doesn’t have to be this way for mid-career and older workers. Community colleges can develop academic programs that prepare these workers for higher-wage, higher-demand jobs while they still have time to recover from periods of diminished wealth accumulation.

In fact, it is likely more imperative to recruit and train older workers, who may naturally be less inclined to switch jobs or careers. That’s not to say it is unnecessary to offer similar opportunities to younger workers. But older workers are much closer to the day when they can no longer work, and nearly half of them are behind the eight-ball.

Community colleges could be problem-solvers, but it means recruiting mid- and late-career workers into programs specially designed for them. It also means eliminating training programs for low-wage jobs that have no potential to help workers at any age save for retirement.

Photo Credit: Nenad Stojkovic, via Flickr