Education researchers have touted microcredentials as the next big thing in post-secondary education, but a new survey of more than 500 employers indicates that they raise a lot of questions but provide few answers. Learners earn a microcredential after completing a short, competency-based, non-credit training course. The courses typically cost less than college credits and often deliver “anytime, anywhere” education.

The problem with microcredentials, as the survey points out, is that employers don’t know what to do with them. Although the majority of employers (69%) say they are “extremely or very familiar with” non-credit credentials, few know how to interpret them or assess their quality as they relate to the employer’s hiring needs.

Additionally, although some people promote microcredentials as potential substitutes for post-secondary degrees, there is no evidence that non-credit coursework leads to hiring in the way a college degree does. Shortcomings of this approach include a heavy focus on what may amount to developing niche skills and little in the way of coordination or advising regarding what courses to combine.

An EdResearcher study that looked at the issue from the learner’s perspective turned up some interesting finds. The overwhelming majority of people who have completed a non-credit course (94%) report that they learned something new.

Which is a low bar for education, if you really think about it.

The EdResearcher study also found that three-fourths of the students in the study already had at least a bachelor’s degree, and more than 40% had a graduate-level degree. In other words, the majority of learners in the EdResearcher study had already learned how to learn.

Microcredentials don’t make good substitutes for degrees

The value of non-credit coursework is less clear for students who have not earned a degree. Part of the value of a degree is that the institution that awards it is accredited by an agency whose job it is to set quality standards for educational degree programs. In other words, accrediting agencies act as watchdogs to demand that an institution present evidence of its academic rigor and demand proof that its teachers are qualified in their subject matter.

That all gets tossed out the window with microcredentials, and employers are stuck wondering what to do with them. With no accrediting agency to vouch for either the quality of the credential itself or the quality of the issuer, few employers accept this coursework at face value. That seriously undercuts the value of the credential as a recognition of a person’s subject-matter expertise.

And the earner’s perception that completing a course improves their job performance could simply drive the rush toward microcredentialing. (It may or may not; however, there is little evidence to back up that statement.) Likewise, microcredentials could be little more than marketing gimmicks designed to increase a product’s user base or market penetration.

Unless those who offer microcredentials also develop a way to authenticate and evaluate them, microcredentials are likely to have limited influence on employers looking for verifiably trained and educated workers. This seems like an opportunity for community colleges to strengthen their educational programs, as long as they don’t fall into the trap of delivering certificates of little value themselves.

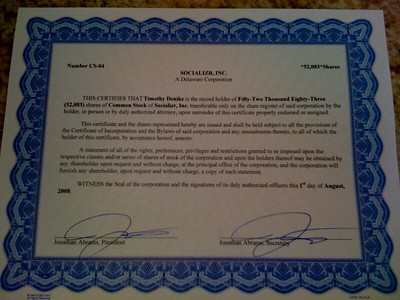

Photo Credit: Timmy Denike, via Flickr