Despite the US labor market being at full- or near-full employment, one-eighth of adult workers made less in the month of September than they did in the previous month. The same poll, which Morning Consult conducted, revealed that one in five high-earning adults (with incomes that exceed $100,000) expect to see their income fall within the next four weeks.

Additionally, the number of workers who logged more than 35 hours of work per week in September fell to 46.7%, a level not seen since the spring of 2021. Year-over-year, the decline in hours worked was 12%. Respondents most frequently attributed the decline to softening market conditions.

The number of workers actively seeking new jobs rose to match levels last recorded three years ago. That’s good because the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that employers added a whopping 336,000 new jobs in the month of September. That shocked economists who expected to see softening labor demands and reduced job creation.

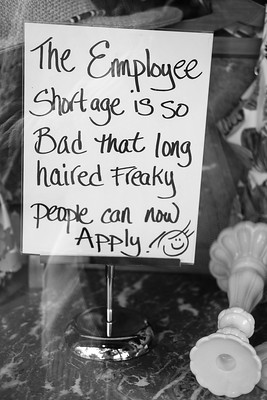

The leisure and hospitality sectors created much of the new job growth. Employment among food and beverage workers has returned to February 2020 levels, but the accommodation sector has not yet fully recovered. Employment in the government sector is also growing, as is employment in education and healthcare.

The unemployment rate has not changed substantially from August 2023. Neither has the number of people who are looking for work, nor the number of long-term unemployed persons. That’s not great news for community colleges hoping to entice adult workers into their classrooms. Aside from falling wages (which seems to be happening largely among high-income workers), there is not much to entice prospective students into the classroom to train for mostly low-wage employment.

High-wage, high-demand occupations will drive meaningful employment gains

Community colleges must do a better job of predicting the demand for workers in higher wage jobs. They must also recognize that to entice an adult worker into the classroom, the payoff must be a better salary than what they’re currently making. Earning a degree also must put them on a better, long-term economic trajectory.

Adult workers cannot afford to take a pay cut – even a small one and even for a short duration. They cannot afford to move backwards economically, so community colleges must offer programs that lift workers and their families into the middle class. Right now, that’s approaching $50,000. Programs that don’t meet those minimum thresholds should be eliminated. That elimination should happen regularly to ensure that the College’s catalog is kept up-to-date and that the College isn’t promoting programs that don’t enable graduates to earn a living wage.

These standards aren’t hard to meet, but they do take effort and investment in instruction. Spending half of the budget on instruction – which is a common approach in community college budgeting – simply may not be enough. Community college administrators must set aside additional funds every year to invest in the development and launch of new, high-wage, high demand programs. That investment could include course and program development, but it could also include capital funds to rehabilitate existing academic space to accommodate new programs.

This kind of investment isn’t happening right now, or consistently, or at the levels required to sustain enrollment growth over time. That speaks to the long-term disinvestment in instruction, and the failure to protect instructional spending from the ravages of inflation. If increasing instructional spending isn’t possible, then it’s all that much more important to eliminate funding for non-productive programs, so the money can fund new initiatives instead.

Photo Credit: Diane M. Schuller , via Flickr